The National Security and Investment Act 2021: Practical considerations for Venture Capital and Private Equity Investments

By Dylan Kennett, Alistair White, and Coran Darling

On 4 January 2022, the National Security and Investment Act 2021 (the “NSIA”) was enacted, establishing in the UK a standalone statutory regime to permit government oversight and intervention in acquisitions and investments on the grounds of national security. This replaces some of the Government’s pre-implementation powers of intervention under the Enterprise Act 2002, allowing more effective governance of investments into companies and sectors of importance.

Much of the advice currently available is sector specific or in relation to later stage investments and acquisitions (for example, DLA Piper’s podcast, Understanding the UK National Security & Investment Regime, which provides a legal overview of the regime and deals with the main sectors impacted, can be found here). Suitable guidance within the context of early-stage and venture capital investment however continues to be a gap for many within the industry.

On 4 March 2022, the British Private Equity & Venture Capital Association (“BVCA”), an industry body and public policy advocate for the private equity (“PE”) and venture capital (“VC”) industry in the UK, released a new set of guidance (the “Guidance”) to assist firms in navigating the new environment during early stages of investment.

In this update, we expand on a number of the aspects raised by the BVCA and considers the potential impact the NSIA has on early stage investments.

The importance of the NSIA to Venture Capital and Private Equity

The reach of the NSIA is broad and it is therefore necessary to consider whether a VC or PE transaction falls within its grasp. Investors are able to do this by considering a number of factors.

Date of investment:

Transactions that closed on, or after, 12 December 2020, but before 4 January 2022 fall within the remit of the NSIA, but in a more limited manner to those which complete or completed on or after 4 January 2022. For clarity, this article considers only transactions which complete or completed on or after 4 January 2022 (those under the regime as implemented in full).

Qualifying acquisitions:

Parties to a VC and PE transaction must firstly consider whether the acquisition or investment falls within the ambit of the NSIA. A qualifying acquisition involves the satisfaction of three conditions:

- the acquisition or investment is of a right or interest in a “qualifying entity” or “qualifying asset” – an assessment here this is relatively straightforward: a qualifying entity is any entity other than an individual, for example a company, LLP, or trust. A qualifying asset in this context includes land, tangible moveable property, and IP.

- the entity or asset is from, in or has a connection to, the UK – this condition is very broad and could include, for example, the acquisition of a factory in France which produces vaccines for use in the UK; and

- the level of control one acquires over the qualifying entity or qualifying asset meets or passes a certain threshold – here this condition will be satisfied if the acquirer:

- takes a shareholding or voting interest in the target that crosses the 25%, 50%, or 75% thresholds;

- acquires voting rights that allow it to pass or block resolutions; or

- acquires an interest which allows it to “materially influence” the policy of an entity or direct the use of an asset. This concept is the same as that used in UK competition law, with the relevant consideration being whether the acquirer or investor can materially influence the management of a target’s business, including its strategic direction and its ability to define and achieve its commercial objectives.

Mandatory versus voluntary:

If an acquisition or investment is a “qualifying acquisition”, further consideration must be had of the mandatory and voluntary parts of the regime.

Turning to the mandatory part of the regime first: parties will be legally required to notify the Government about qualifying acquisitions of entities in 17 sensitive areas of the economy and will be require clearance before completion. These areas are those where the Government considers there are enhanced risks to national security, namely:

- Advanced Materials

- Advanced Robotics

- Artificial Intelligence

- Civil Nuclear

- Communications

- Computing Hardware

- Critical Suppliers to Government

- Cryptographic Authentication

- Data Infrastructure

- Defence

- Energy

- Military and Dual-Use

- Quantum Technologies

- Satellite and Space Technologies

- Suppliers to the Emergency Services

- Synthetic Biology

- Transport

The exact scope of these areas is prescribed in significant detail in secondary legislation and related guidance. Failing to notify a qualifying acquisition in a mandatory sector will result in the acquisition or investment being void. Further, there are related civil and criminal penalties, detailed below.

Turning to the voluntary part of the regime, if an transaction is a “qualifying acquisition” in an area outside of a mandatory sector, or is an acquisition of assets within a mandatory sector, then it will be subject to the voluntary regime. Here, there is no obligation to inform the Government of the transaction. However, if the Government reasonably suspects that it might give rise to a national security risk, it may be “called-in” for review. The Government will be able to assess acquisitions for up to 5 years after they have taken place and up to 6 months after becoming aware of them if they have not been notified.

Consequences of non-compliance:

Failure for investors to appropriately consider whether their investment activity falls within the remit of the NSIA, and therefore failing in carrying out their subsequent obligations under the regime, can be substantial, leading to both civil and criminal sanctions. As noted above, if the investment or acquisition involves a mandatory sector but does not comply with the mandatory notification provisions prior to closing, the deal is void.

In instances of non-compliance with the regime, investors may also be subjected to severe penalties, including:

- fines of up to £10 million or up to 5% of global turnover, whichever higher; and

- up to 5 years imprisonment for directors of the investor firms.

Further, should investors or acquirors in voluntary sectors fail to notify under the voluntary regime, the Secretary of State may still (even retrospectively) intervene and impose remedies to protect national interests. These may include conditions restricting access to sensitive sites, restriction of access to confidential information, and the prevention of transfers of valuable assets, such as IP.

Failure to comply with the regime therefore poses a significant shared commercial risk for both acquirors/investors and the target company.

Immediate impacts on Venture Capital and Private Equity transactions

While the implementation of the NSIA appears to increase restrictions and hurdles on investments, particularly those at earlier stages where funding is drawn from a number of sources and geographies, the Government has emphasised that the UK remains open for investment. Instead, the provisions in the NSIA are merely viewed to take a proportionate approach to mitigating the risks of national security in the wider geopolitical context.

Despite the optimism of the Government, it remains clear that the act is set to impact the VC and PE industry in a number of forms.

Difficulty in determining qualifying transactions:

As part of the notification requirements under the NSIA, it is mandatory for parties to notify the Government in the event their transaction falls within the 17 designated mandatory sectors, which can broadly be categorised within the following:

- critical infrastructure (such as defence and energy);

- advanced technologies (such as dual-use technology and artificial intelligence); and

- critical suppliers (such as those contributing to government or emergency services).

For more established investment targets, it is often easier to determine the parameters of their activities and assets, and therefore determine whether one of the mandatory sectors are engaged. For early-stage entities or those involved in innovative activities, however, it is often more difficult to ascertain whether operations fall within a mandatory sector. This is particularly the case for early-stage technology targets who are likely to be fluid in their developments, pivot often or yet to have a clear target area of the market for which they wish to establish themselves. The ability to comply with the provisions governing early-stage investment and determine whether a transaction qualifies under the regime is therefore made more complicated and will likely lead to confusion moving forwards.

Parties involved should therefore be aware of the nature of target investments and, when in doubt, have the target confirm these details more specifically during due diligence.

Regulatory uncertainty

One of the most notable impacts of the NSIA is the detail in which the definitions go into with respect to the potential activities of organisations. It can therefore take prospective investors substantial time to assess whether they fall within the remit of the framework. Many of these definitions and their practical implications are also yet to be tested, and therefore investors may not fully understand the extent in which they attach to their potential investments; a chilling effect on investment in UK companies may also be an issue caused by this uncertainty.

By virtue of the NSIA acting as a foreign direct investment regime, the framework also has the ability to flex, based on which foreign entities the Government seeks to permit or exclude at a given time. It may therefore be difficult for organisations to determine the extent to which the current Government might object to their investment. In order to clarify its position, the Government has released a statement of intent detailing the types of factors it will consider in its reviews and the rationale behind its current position. While this does provide context to its decision making, it remains the case that its application of the NSIA can evolve to meet the needs of national security as they arise, which inherently increases uncertainty for investors.

A risk-based approach, considering the context of each matter, should be taken in order to identify any areas of potential ambiguity within an acquisition. This will allow parties to map out any areas of uncertainty and determine whether the acquisition is commercially viable when balanced against its risk profile.

Timings & Associated Costs

A further added impact parties must consider is the effect the NSIA will now have on timings of their investments. For transactions which fall within the voluntary part of the regime, it may be wise for parties to alert the Government of a potential qualifying acquisition. Once this has taken place, or if notification is mandatory, over the course of 60 days the Government will determine whether to impose remedies or take no further action with respect to the investment (this is split into a two phase process and is subject to extension in some limited circumstances).

Parties should be cognisant of the potential for costs to increase during this period or for the transaction to remain in a state of purgatory until a decision can be made. Further, in the initial analysis phase of determining whether to invest, parties should be cognisant of the additional costs of associated advisers in determining whether a transaction falls within the regime. This adds another layer of costs to parties, where fee certainty is essential in venture capital given early stage companies are less able to bear additional fees. Albeit the Government wants to see the UK as a hub for innovation, it has perhaps inadvertently put the load on those who are least able to shoulder the burden.

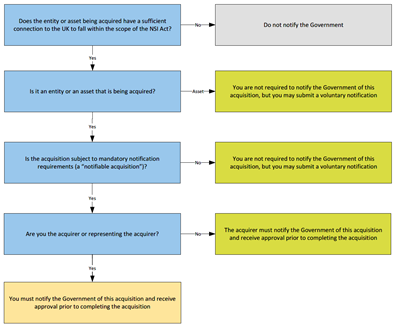

Flowchart of considerations

A simplified flowchart of considerations when determining whether to notify the Government of the transaction can be found in the diagram below:

Source: BVCA Guidance. Page 12.

As noted above, further details on the provisions of the NSIA and its impacts on the wider investment sector can be found in DLA Piper’s podcast, Understanding the UK National Security & Investment Regime, which can be found here.

Secure Innovation and emerging technology investment

For those interested in continuing their investments into these sectors, additional guidance has been provided in the form of Secure Innovation (“SI”). SI is a creation of the partnership between the Centre for the Protection of National Industries and the National Cyber Security Centre, designed to help support emerging companies and private capital investors navigate the new security framework and build inherent security from early on.

The purpose of SI is to offer advice on how best to engage with the security of companies with which investors may wish to become involved. As part of their work, SI have produced guidance on how best to navigate this including:

- Questions to ask during investment;

- Means of securing supply chains;

- Managing risks from additional collaboration; and

- Expanding into new markets and attracting further investment.

It is recommended that this be read alongside the BVCA resources in order to ensure all potential risks to prospective investments are considered.

If you have any questions regarding these developments, please contact the authors or your DLA Piper relationship attorney.

This information does not, and is not intended to, constitute legal advice. All information, content, and materials are for general informational purposes only. No reader should act, or refrain from acting, with respect to any particular legal matter on the basis of this information without first seeking legal advice from counsel in the relevant jurisdiction.

Download PDF